A Dangerous Road

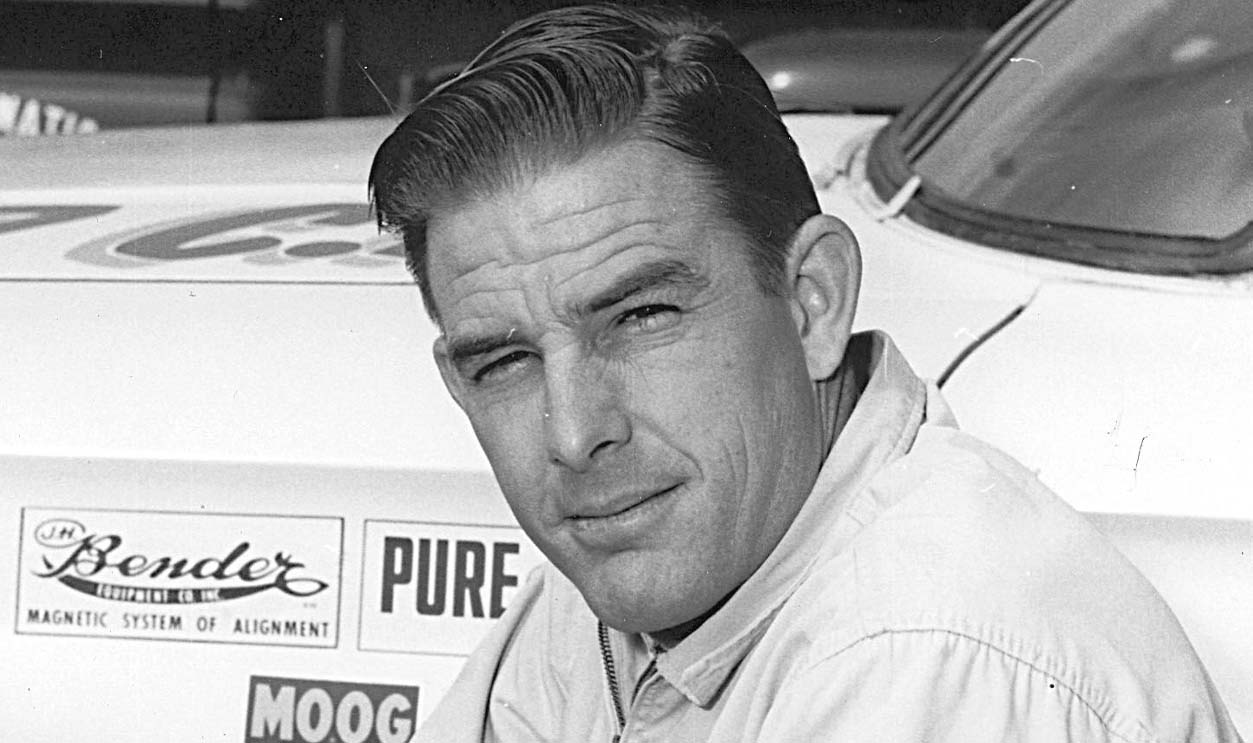

Larry Mann was the first driver to die in a NASCAR Cup Series event. Racing was dangerous in the 1950s. Add in dubious weather and an infamously unforgiving track, and the stage was set for tragedy—and perhaps that tragedy was made even worse when Mann dared to spurn a superstition that had been entrenched for decades.

Behind The Mask

“Larry Mann” was the racing name of Lawrence Zuckerman, a New York mechanic whose NASCAR career started in 1952—and ended the very same year. Not much is known about his early life, but it’s thought that being Jewish, he adopted a competition pseudonym to avoid prejudice.

Extraordinary Ordinary

Stock car racing meant NASCAR racing even in those days. NASCAR had been around for just a few years when Mann got involved. It was a sport that seemed available to anyone, making use of ordinary cars modified for speed and sizzle, with some history behind it too.

Speeding Along

The story goes that during Prohibition and after, moonshine smugglers would modify their “stock” cars to outrun the police and add extra space for transporting more of their popular merchandise. And in their off time, they’d race their augmented autos for bragging rights.

History of NASCAR, WatchMojo.com

History of NASCAR, WatchMojo.com

Stock Story

Stock cars were supposed to be modifications of cars anyone could buy at a dealership (or had bought there, if it was a used car). Although NASCAR would increasingly distance itself from that definition, when Mann competed, stock cars still very much had that “in stock” quality.

1952 Motor City 250, NascarAllOut

1952 Motor City 250, NascarAllOut

When Good Cars Turn Bad

But even ordinary cars could turn nasty with massive tweaking, high speeds, and questionable tracks. The risk to drivers (and spectators) could be immense. That was the case on a smooth track, and races were even riskier on unpaved dirt roads that got mashed up more and more after every car’s latest lap.

1952 Motor City 250, NascarAllOut

1952 Motor City 250, NascarAllOut

NASCAR On Top

From its inception in 1948, stock cars and NASCAR have gone hand in hand, and what’s now known as the NASCAR Cup Series has been the top tier of that top tier. When Mann entered the 1952 season, this top level was known as the NASCAR Grand National Series.

1952 Motor City 250, NascarAllOut

1952 Motor City 250, NascarAllOut

Enthusiastic Start

We can’t know how far Mann would have advanced in the Grand National Series in later years, because he was the first driver to die at this top-tier level. But he dove into competition with some enthusiasm, traveling to various racetracks to prove himself in this raw and risky sport.

Driving A Nash

Mann’s NASCAR debut took place at the Langhorne racetrack in Pennsylvania, where he drove a Nash on a spring day in May. Nash was one of the various car companies that took a keen interest in stock car racing, later merging with Hudson, to which Mann turned for his later races.

1952 Langhorne Grand National 250 (Colorized), NascarAllOut

1952 Langhorne Grand National 250 (Colorized), NascarAllOut

No Right Turn

Langhorne could be a challenge. It was a dirt track, more or less circular, that drivers unaffectionately called the “Big Left Turn”. It was a nerve-racking, gear-smashing nightmare, with drivers never sure who was around the corner and who was on their tail.

1952 Langhorne Grand National 250 (Colorized), NascarAllOut

1952 Langhorne Grand National 250 (Colorized), NascarAllOut

Heading South

Mann didn’t exactly make headlines in that nightmare scenario, coming in just 27th out of 37 starters. But Mann didn’t confine his ambition to the Langhorne track. Switching to a year-old Hudson Hornet, he competed in the Southern 500 but ended up just 55th out of 66 cars.

Lars-Göran Lindgren Sweden, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Lars-Göran Lindgren Sweden, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Keeping It Low

Mann wasn’t the only driver with a Hudson Hornet. Its manufacturer was the first to support stock car racing, and the results were clear. Hudson cars won 27 of the NASCAR Grand National’s 34 cars in 1952. A lower center of gravity particularly improved handling.

1952 Motor City 250, NascarAllOut

1952 Motor City 250, NascarAllOut

Getting Better

Mann did do better at the Monroe County Fairgrounds in Rochester, New York, his best result in the NASCAR Grand National Series, but even then, he finished just 11th. In fact, through his six races, he managed to earn just $135. Stock car racing wasn’t proving to be the road to riches.

Back Again

On the 27th race of this NASCAR Cup Series, Langhorne Speedway was again the host. 20,000 spectators prepared to watch drivers literally drive around in circles to see who would triumph, not just overall, but against the worst part of the track—known as “Puke Hollow”.

1952 Langhorne Grand National 250, NascarAllOut

1952 Langhorne Grand National 250, NascarAllOut

Danger Abounds

Dirt, dust, and washboard slats competed with potholes to swallow up cars, except when they were being tossed into the air. Opened in 1926, the track would petrify drivers for decades. Three of the first four NASCAR World Cup Series fatal crashes happened at Langhorne.

1952 Langhorne Grand National 250 (Colorized), NascarAllOut

1952 Langhorne Grand National 250 (Colorized), NascarAllOut

Sideways Move

By 1957, NASCAR had given up on the track. Promoters decided improvements would be in order, so around 1964, the track was paved and the O-shape turned into a D-shape. But it was a mixed bag, as cars with engines in the back could go even faster, and slip-slide sideways.

1964 NASCAR Riverside MotorTrend 500, Sandeep Banerjee

1964 NASCAR Riverside MotorTrend 500, Sandeep Banerjee

Challenging Opinion

This was particularly alarming as Langhorne had long been the fastest track with one-mile laps—and that was when it was unpaved. Yet not every driver objected to more speed. AJ Foyt relished the challenge of racing on “a track that separated the men from the boys”.

Peter Hamer, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Peter Hamer, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Free Parking

Then came another pavement job—in the 1970s, to turn the speedway into a shopping mall’s parking lot. Before its demise, the track had earned such a bad reputation that USAC drivers boycotted the track in 1971, helping to close the oval that had recorded a total of 27 fatalities.

The Beginning Of The End

But back in 1952, this track was unpaved, and it was time for drivers to risk their lives and reputations once again. Mann and 43 other drivers sped off, furiously advancing lap by lap—until tragedy struck on Mann’s 211th lap. And it was near that infamous Puke Hollow.

1952 Langhorne Grand National 250 (Colorized), NascarAllOut

1952 Langhorne Grand National 250 (Colorized), NascarAllOut

Shaking Violently

Paul Smith drove the speedway over the years, and said Langhorne was bad on a motorcycle and even worse in a stock car. One time, he was in the lead, “but it was so rough through Puke Hollow that the gas tank shook right out of the car,” he recounted. Mann would suffer worse.

1952 Langhorne Grand National 250 (Colorized), NascarAllOut

1952 Langhorne Grand National 250 (Colorized), NascarAllOut

The Deadly Crash

That slippery day in 1952, Mann’s Hudson Hornet went out of control, ramming a steel guardrail and slicing a fence. Newspapers said the car flipped three times, the battered vehicle coming to a crushing stop against the limbs of some trees. It would be hard to imagine anyone surviving.

Ominous Signs

But Mann was alive for now, even after a crumpling chassis had pounded his head and body, unleashing a pulmonary hemorrhage. As his lungs filled with blood, Mann’s fate looked precarious. And a superstition that had long spooked racecar drivers seemed confirmed.

1952 Unknown driver flip @ Langhorne, NascarAllOut

1952 Unknown driver flip @ Langhorne, NascarAllOut

No Caution

Rescuers extracted Mann from the wreckage of a car ominously painted green. Apparently out of defiance, not ignorance, Mann had violated racers’ superstition that no car painted that color should dare to expect to reach the finish line. And it was a fear that stretched back decades.

1952 NASCAR Cup @ Langhorne - Wilkes Flips/Eubanks Big Crash, Racing Archive

1952 NASCAR Cup @ Langhorne - Wilkes Flips/Eubanks Big Crash, Racing Archive

Where It Started

In a curious coincidence, Gaston Chevrolet was also 28 when he passed, having crashed his green Frontenac at the Beverly Hills Speedway in 1920, just months after he’d won that season’s Indianapolis 500. Drivers shuddered. But more logical reasons could be cited in 1952.

Le Miroir des sports, Wikimedia Commons

Le Miroir des sports, Wikimedia Commons

A Deadly Trend

10 drivers had already perished at the Langhorne Speedway over the years, albeit none at a NASCAR event—but the racetrack would soon prove deadly to other NASCAR drivers, not just the unlucky Mann. Frank Arford would die in 1953, and John McVitty would perish in 1956.

1953 Langhorne Speedway race | NASCAR Classic Full Race Replay, NASCAR Classics

1953 Langhorne Speedway race | NASCAR Classic Full Race Replay, NASCAR Classics

On The Edge

But on this late summer day in 1952, it was Mann’s life at risk as his failing body was raced to nearby Philadelphia’s Nazareth Hospital to try to save him. And as if that wasn’t tormenting enough, another driver at that very same competition hung between life and death.

1952 NASCAR Cup @ Langhorne - Wilkes Flips/Eubanks Big Crash, Racing Archive

1952 NASCAR Cup @ Langhorne - Wilkes Flips/Eubanks Big Crash, Racing Archive

Not Very Sunny

Langhorne was a dirt track, in an oval shape, each lap measuring one mile. The first turn was the most treacherous, especially when fast tires met wet road, and September 14, 1952, had been a rainy day. Five other drivers crashed that day, and one of them was struggling to live.

1952 Langhorne Grand National 250 (Colorized), NascarAllOut

1952 Langhorne Grand National 250 (Colorized), NascarAllOut

A Tale Of Survival

Nelson Applegate, a New Jersey driver, had his head banged up so badly in a crash he too lay in hospital, his prognosis uncertain. Despite fears that this day would see two NASCAR drivers meet the grimmest of fates, Applegate survived, but barely. Mann’s luck, however, was running out.

1952 NASCAR Cup @ Langhorne - Wilkes Flips/Eubanks Big Crash, Racing Archive

1952 NASCAR Cup @ Langhorne - Wilkes Flips/Eubanks Big Crash, Racing Archive

No More Laps

Despite doctors’ heroic efforts, the NASCAR neophyte’s body could hold on no more, fatally stung by the car he’d affectionately dubbed the “Green Hornet”. Named after a masked crusader against crime and injustice, this Green Hornet would prove to be Mann’s undoing.

1952 NASCAR Cup @ Langhorne - Wilkes Flips/Eubanks Big Crash, Racing Archive

1952 NASCAR Cup @ Langhorne - Wilkes Flips/Eubanks Big Crash, Racing Archive

First And Not Last

Mann passed that very evening, to the shock of racing fans across the nation. The 28-year-old’s death in 1952 would be the first of 28 drivers to perish at NASCAR Cup Series events, the last being Dale Earnhardt at the Daytona 500 in 2001, thankfully decades ago.

Darryl Moran, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Darryl Moran, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Family Grieves

Meanwhile, Mann’s resting place would be Montefiore Cemetery in Queens County, New York, as his wife and children grieved their husband and father. But obscurity would not be this family’s fate, as his daughter, five years old when her father passed, would see fame and tragedy herself.

Antony-22, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Antony-22, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Taking The Tour

Widow Abby Zuckerman took her two children and moved about, eventually ending up in Los Angeles. She knew something of show business, having booked gigs for famed musical conductor Leonard Bernstein. And her daughter would also explore the entertainment world.

Allan warren, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Allan warren, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

On The Move

Barbara Ellen Zuckerman won a scholarship to the California Institute of the Arts. After graduation, she moved back to New York to pursue her passion as a folk singer. But she would eventually find a new home, Vancouver, British Columbia, and a new name, Babz Chula.

Babs Chula - Playing in Bands, Conversation SnapShots

Babs Chula - Playing in Bands, Conversation SnapShots

Big And Small

Her first major role was in the acclaimed film My American Cousin (1985), and for the next 25 years, she would be a major presence in the local acting and singing scene. Besides movies, she also appeared in TV shows, including Final 24, which would be her last television role.

Cineflix, Final 24 (2006–2007)

Cineflix, Final 24 (2006–2007)

Final Act

By the time that episode aired in 2007, Chula was embroiled in her own battle against death, albeit at a much slower pace than her father had faced. Chula had cancer, and a National Film Board of Canada production chronicled her search for a cure that stretched over six years.

Chi Official Trailer: Can Ayurveda cure cancer?, DocuBay - Streaming Documentaries

Chi Official Trailer: Can Ayurveda cure cancer?, DocuBay - Streaming Documentaries

Grief Strikes Again

The film particularly focused on her journey to India, but despite her efforts, Chula passed in 2010, aged 63. Featuring Chula’s last film role, as herself, Chi came out in 2013, allowing director Anne Wheeler to include her grieving family’s thoughts about her life and her successes.

Poor Reward

But her father’s death was a critical point in Chula’s life. And even if Mann had survived that horrific day, his reward would have been paltry. In a points system that didn’t require drivers to reach the finish line, Larry Mann “finished” 22nd on that fatal day, and would have received $35.

1952 Langhorne Grand National 250 (Colorized), NascarAllOut

1952 Langhorne Grand National 250 (Colorized), NascarAllOut

Better Results

And curious numbers pop up again in a tale of who won that deadly race in 1952. Lee Petty was the grand patriarch of stock car racing, father of future racing legend Richard Petty, who would one day race in cars bearing #43, the same number Mann displayed that deadly season.

us44mt, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

us44mt, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Color Of Fear

And the superstition against green has been slow to fade. Darrell Waltrip resisted driving a white-and-green car sponsored by Gatorade. He did give in—and survived to tell the tale. Tim Richmond, however, insisted on a regular Folgers look, as decaffeinated green just wouldn’t do.

Billferguson, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Billferguson, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Exit Ramp

So, it's clear that stock car racing in the 1950s was dangerous. Larry Mann was caught up in an atmosphere of NASCAR risk and danger. On a perilous track on a rainy day, Mann lost his life in a sport that has long since changed—but too late to get this New Yorker across the finish line.

You May Also Like:

Formula 1’s First Grand Prix Victim

F1 Drivers Who Died On The Track

NASCAR Drivers Who Died On The Track

Florida Memory, Wikimedia Commons

Florida Memory, Wikimedia Commons

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19