A Career Cut Short

Onofre Marimón was a rising star on the Grand Prix circuit when he became the first driver to die at a Formula One Grand Prix event. Here’s the story of Marimón’s rise to fame in Argentina and the waves he made in the European racing scene, until a bit of daring led to a tragic end.

Runs In The Family

Onofre Marimón was born in 1923 into the world of auto racing. At the age of 13, he reputedly snuck his father’s two-seater out of the garage and took it for a spin—a very fast spin. When he returned home, he bragged about his feat to his mother, who proceeded to smash a dish on his head.

Like Father, Like Son

His father, an undertaker and racing enthusiast, was apparently more encouraging. Domingo Marimón had driven in many Turismo Carretera races, including the 1948 Gran Premio America, covering 5,950 miles (9,576 km) from Caracas to Buenos Aires. But his son’s time would soon come.

Early Victory

Just a year later, Domingo fractured his collarbone, so 26-year-old Onofre took his father’s 1939 Chevrolet and dove into the Mar del Plata endurance race. Six laps and 536 miles (864 km) later, he and fellow driver Gabriel Braulio Ortega won, averaging 74 miles per hour (118 km/h).

Signs Of Danger

This was a tremendous victory for Marimón in his very first race, but there were plenty of reminders of how dangerous the sport could be. Of 94 cars at the start, only 28 finished—and death struck on the very first lap when Matías Fernández drove off the road and overturned.

Teammate And Friend

But things were looking up for Marimón. Not only had he come first at Mar del Plata, he came in second at La Cumbre, a race won by famed racer José Froilán González, who would soon be a teammate and friend, and who’d beat Onofre to the European Grand Prix scene by a year.

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Another Victory

Before a race the next year, Domingo said whoever was faster in practice would drive his car. Onofre beat his dad’s time, earned pole position, and then won the race—one of seven victories in 1950. And only engine trouble foiled likely victory against Juan Gálvez at Vuelta de Córdoba.

Across The Ocean

The next season saw Marimón win La Cumbre, and do well in other Argentine races, but Marimón’s sights were set far away. His father’s friend and fellow driver Juan Manuel Fangio had promised to mentor the son, paving the way for Onofre’s bittersweet European debut.

Bjørn Fjortoft, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bjørn Fjortoft, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Racers Reunited

Marimón entered the 1951 Le Mans, a grueling stock-car competition so long that getting to the finish line required a driving partner. Marimón teamed up with the man who’d kept him from first place just two years before, José Froilán González. But a radiator burst their chances after 128 laps.

Geoff Charles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Geoff Charles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

World Championship Debut And Disappointment

Just a week later came another chance—at Marimón’s first-ever World Championship race. The eager driver piloted a Maserati 4CLT-50 at Reims, but sadly, its motor conked out, and with it Marimón’s path to victory. But fellow Argentines Fangio and González came in first and second.

Geoff Charles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Geoff Charles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

On The Sidelines

Marimón joined his great friends Fangio and González at the British Grand Prix, though only as a spectator. González’s Ferrari and Fangio’s Alfa Romeo came in first and second respectively. Later in 1951, Marimón came in eighth at a Modena Formula Two race, marred by pit delays.

Geoff Charles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Geoff Charles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Mixed Tally

So, by the time Marimón returned to his homeland that year, he’d started to make a name for himself, but hadn’t captured any crowns. There was potential, but results were still mixed. In 1952, he was back in his dad’s Chevy for the Mecánica Nacional, but he didn’t quite win it.

Geoff Charles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Geoff Charles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Making Plans

Marimón also had a wife and two children to support. Staying in Argentina for most of 1952, he prepared for the next phase of his European career, and opened a car dealership. He was also known to give books and toys to children of his town when he came back from his travels.

Geoff Charles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Geoff Charles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Europe Calls

Marimón ended the season at the Gran Premio de Montevideo, but finished only sixth in a Ferrari 125. Then, in 1953, he joined a non-championship race at the Gran Premio Ciudad de Buenos Aires. But he came in only tenth in a Ferrari 166 F2. However, Europe still beckoned.

Tests Of Endurance

Marimón faced tests of endurance once back in Europe, and it was the machines that couldn’t endure. Like the name suggests, Mille Miglia was an Italian race that ran 1,000 miles (1,609 km). But the Alfa Romeo 1900TI he and Gianfranco Moroni drove never made it to the end.

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Another Disappointment

Next was the 24-hour Le Mans, judged on distance covered in a day, favoring durable and reliable cars. Driving partner Fangio managed just 22 laps in an Alfa Romeo 63 3000CM before engine trouble cut them short. Marimón hadn’t even had a chance behind the steering wheel.

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Maserati Debut

But Fangio had convinced Maserati to take Marimón on board, at least as a test. His first Grand Prix with the team took place at Spa, just a week after that disappointing race at Le Mans. At practice, teammates Fangio and González came in first and third, with Marimón back in sixth.

Teammate Trouble

On race day, González quickly took the lead, but on the 11th lap, his gas pedal broke, putting him out of action. Fangio’s engine then conked out, but the driver switched cars and got back into the race. Meanwhile, Marimón sped into third place, then second—but it looked like trouble was about to strike.

Geoff Charles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Geoff Charles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Pushing On

It looked to Marimón that his motor would conk out. He pulled into the pits, but was ordered to get back into the race and push on. In the final lap, Marimón’s chance at a podium position seemed in doubt as three cars were ahead of him. But trouble struck teammate Fangio again.

At The Podium

Fangio was in second place when his steering gave out, sending him crashing into a ditch. Fortunately, he wasn’t seriously injured, but with him out of action, Marimón was able to cross the finish line in third place. Maserati was impressed, and signed him up for the rest of the year.

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Sad News From America

In between Mille Miglia and Le Mans came news that Chet Miller had died during a practice run at the Indianapolis 500, the first fatality at a World Drivers’ Championship event. But at that point, no driver had died at a Grand Prix competition. That record would soon be sadly broken.

Geoff Charles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Geoff Charles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

More Mechanical Problems

The next two Grand Prix were disappointments for Marimón. A damaged radiator dropped him from sixth to ninth place at Reims, and at his Silverstone debut for the British Grand Prix he was in a tough fight for fifth place when his engine died. He got back into the race, but finished ninth.

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Speed Bumps Ahead

The rough year continued with more bad luck, including an accident at a non-championship race and an engine running too hot at the Nürburgring 1,000-km race, forcing him and Emilio Giletti to withdraw their Maserati A6GCS—frustrating as they’d reached second place on some laps.

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Monza Mess

At the Italian Grand Prix, Marimón drove a Maserati A6GCM, just behind a battling trio including Fangio, but his oil radiator broke down on the 46th lap. He spent eight minutes at the pits and lost three laps. Then he had an accident with five laps to go, forcing him off the Monza track.

Year-End Review

But 1953 ended on relatively good terms. At Modena’s Aeroautodromo, Marimón ended up second to teammate and friend Fangio. As he traveled back to Argentina, he could reflect on a frustrating but busy year, and might have hoped for better in 1954—not realizing that year would be his last.

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Not A Good Start

Marimón was still in Argentina when 1954 began, competing in the Argentinian Grand Prix, but not for long. He was in an accident on the fifth lap, and withdrew his Ferrari 250F. At the non-championship Gran Premio Ciudad de Buenos Aires, he bowed out in the fourth lap.

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Back In Europe

Marimón made his way to Europe and competed in four non-championship races, where he won the Gran Premio di Roma—following races where he came in fourth and fifth, or retired due to suspension problems. Now it was time for his second Grand Prix of the year, this one at Spa.

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Foiled Again

Though he qualified fourth—after Fangio, González, and Italy’s Giuseppe Farina—Marimón dropped out after only three laps, his car’s engine giving up the ghost. Then he tackled another test of endurance, this time at the Gran Premio Supercortemaggiore and its 1,000-km circuit.

Geoff Charles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Geoff Charles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Broken Hopes

Paired with Fangio, the two were in second position when trouble struck on the 152nd lap of the Monza track. The rear axle of their Maserati 250S/6C broke, ending their promising effort. In July of 1954 it was back to Grand Prix races, starting with the French Grand Prix at Reims.

More Trouble

Marimón had qualified fifth on the Reims track, and managed to get into fourth place early on. But his car’s engine misfired, and time in the pits cost him dearly. Then he had to retire by lap 27 due to a gearbox acting up. Next would be the British Grand Prix, but bad luck struck again.

Coming From Behind

Due to a mix-up, Marimón’s car was sent to the wrong port. Robbed of qualifying time, Marimón had to start at the back of the pack at Silverstone. Through sheer force of will and his prodigious skill, he managed to get close to the lead, finishing third in a race that was won by González.

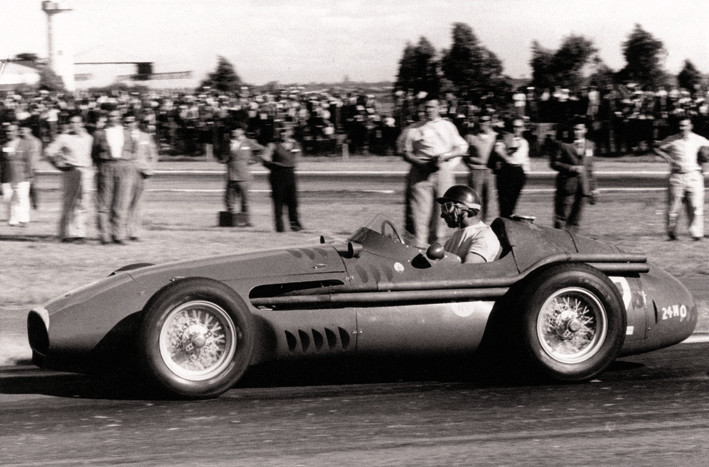

Feeling Too Slow

Two weeks later, it was time for the German Grand Prix at the challenging Nürburgring race course. Marimón felt he was too slow during Friday practice. He asked his friend, mentor, and teammate Fangio what to do. Fangio suggested the two could drive the track together.

Agridecumantes, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agridecumantes, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Heading Out Alone

It was Saturday morning, the end of July, and a cloudy sky threatened a rainstorm. Marimón wanted to drive on a dry track, so he decided to head off without Fangio. Domingo, who was helping man the pits, told reporters later his son had vowed to cover a lap in under 10 minutes.

Geoff Charles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Geoff Charles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Out Of Time

Domingo was timing his son, as he so often did. The 10 minutes came and went. There was no Onofre. “I had a sense of foreboding,” the father would later recount. He would soon learn the horrible news: His son’s car had plunged through a roadside bush and careened down a slope.

Tragedy Strikes

The Maserati 250F eventually stopped rolling, but it was upside down. Rescuers reached the car and freed Marimón, but it was too late. A priest who happened to be in the area came over and administered last rites. González arrived on the scene and felt even more disturbed.

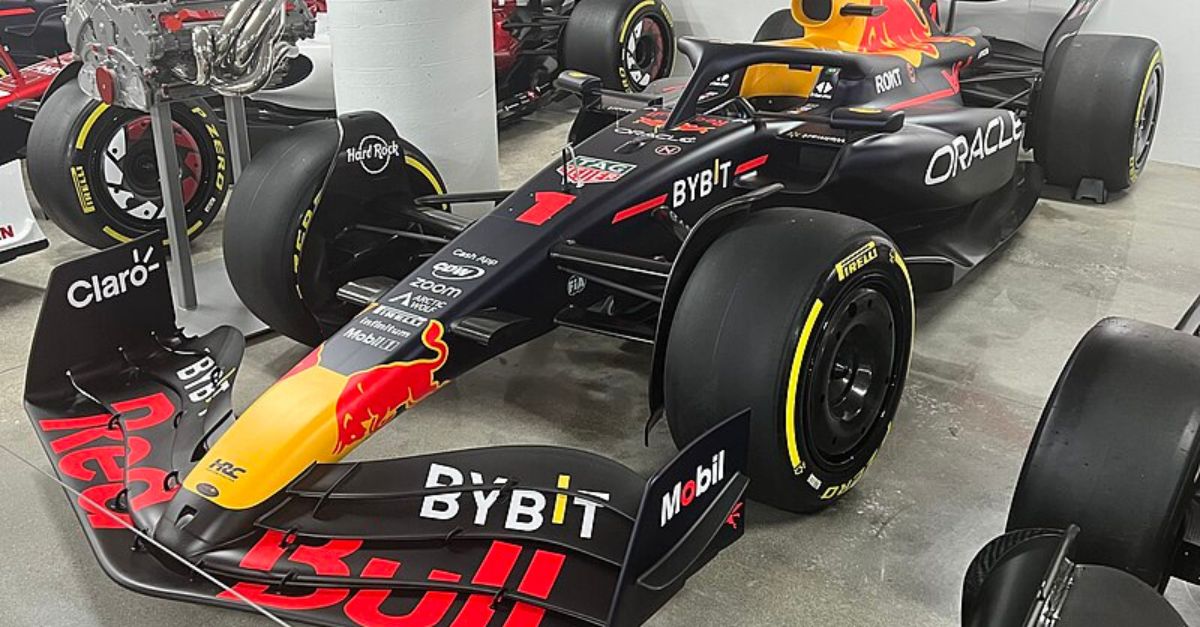

Maserati, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Maserati, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Wrong Gear

The fellow Argentinian noticed the Maserati was stuck in fourth gear, and it was a “third gear” kind of corner that Marimón had failed to navigate. As Marimón was approaching the Adenau bridge, he must have been so determined to beat 10 minutes, he pushed just a bit too hard.

Sad Victory

González drove back to the pits, and broke down as he and Fangio consoled each other. The race would still go on, with Fangio winning the next day. Meanwhile, the body of 30-year-old Onofre Agustín Marimón would make its final journey to the young driver’s grieving homeland.

The Final Finish

It was eventually surmised that a braking unit in Marimón’s car had been the mechanical cause of his death. Marimón, who as a child had been nicknamed “Pinocho” by a cousin, was buried in his hometown of Cosquín, Córdoba, Argentina. A large crowd turned out for his funeral.

Early Promise Cut Short

A driver of great potential, Marimón started in 11 Grand Prix over his short career, winning two podium results and accumulating eight championship points. The Argentinian showed deftness on the race track, and inspired his countrymen, who even today think of him fondly.

Deadly Daring

It was dangerous in the early years, even decades, of Formula One racing. Onofre Marimón’s tragic fate came not from a collision, nor even from an actual race, but from a practice run where the daring driver tried out a stretch of track without his mentor—a decision that proved all too deadly.

You May Also Like:

Incredible F1 Drivers Who Died On The Track

Formula One's Last Fatal Crash Was Its Most Tragic